I don’t know what to make of the cows lowing at night, whether to feel sorry for them or to be angry because of their noisy restlessness. It’s late September in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, the time when calves are carted off and sold. The mothers walk around all night calling their kids. Coyotes bay, taunting the cows as if to tell them they’ve lured their children into the woods and killed them. Maybe they have murdered a calf or two, but it’s unlikely. At least that’s what the farmer who rented us the cottage for two weeks tells me. I can’t sleep through the racket.

My husband, Greg, snores peacefully in our bed beneath the open window. He insists on keeping it ajar even when it’s bone chilling. The fresh air helps him sleep better, he says. I don’t know why he thinks this. His head is buried under the comforter so all he’s inhaling is his own carbon dioxide. I worry he’ll suffocate, and I won’t discover this until morning because I’m encased in flannel pajamas and thick socks and won’t know his coldness means he’s gone.

Between the cows and the coyotes I think I hear someone downstairs in the kitchen, opening cabinet doors, dragging food across the counter. The dog hears it too; she buries herself under my side of the bed and whimpers. I shake my husband awake and tell him what I’ve heard. He gives me a pitying look. He doesn’t want to leave his cocoon, but he doesn’t want to listen to me and the dog whine.

He prepares the mousetrap, spreading peanut butter across the trip lever and placing it in the pantry. He doesn’t say anything or kiss me goodnight. I don’t ask if he thinks a mouse can open the pantry door. I burrow deeper into the blankets than he does.

In the morning, he extracts a carcass from the trap and holds it by its tail, examining it as if it were a gift.

I focus on filling the coffeepot. “Should we throw it in the field?”

He shrouds the gray thing in a white paper towel. “That’ll draw coyotes.” He places the package at the end of the counter next to a stack of cookbooks.

“Trash. We could put it in the trash.”

“Garbage won’t be picked up until the end of the week.”

Although my stomach rumbles, I’ve no desire to eat. Greg sits at the table, caught in the only shaft of light piercing the morning fog. He has chocolate eyes and dark hair and the remnants of a summer tan. He has put up with tears, anger, and ennui. A dot of shaving cream hides beneath his earlobe. “We can put it in the dumpster in town,” I say.

We rented the cottage because we needed something new, a fresh place to put our things, a different bed to sleep in. “Or toss it in the river.” He is my second husband, my lover for five years before we married, the one I wanted to be the one. So much so that at forty I became pregnant. My idea, not his. When I place his bowl of cornflakes on the table, he reaches for my hand, but I spin away.

He snaps open the newspaper. “I’ll take care of it,” he says.

The dog lifts her snout toward the remains. I fill her food bowl.

I walk into the living room so he won’t see me rubbing my stomach. I started doing that in June when I discovered I was pregnant; now I do it to replace what was lost. A long moo rolls across the pasture and through the cottage. Another mother looking for her child. She still doesn’t know she can bellow all day and it won’t make a difference.

After breakfast the dog barks to go out. In the backyard Greg tosses a ball to her. She snatches it in the air and runs back to him. Again and again they do this, neither of them wanting to return inside. The mouse remains laid out on the counter, the outline of his rump and tail visible under his white shroud. The longer it stays there, the more unsettled I feel. In the changing light, I think I see the corpse move. I touch the paper towel; it’s cold. Carefully I slide the wrapped body into a brown bag, and grabbing a wooden spoon, carry it and the bag out the front door.

At least twenty cows silently saunter to the fence to watch me walk down the dirt road. Mucous drips from their eyes and snot flows from their noses. Dust covers my shoes. Every few strides the package bumps against my jeans. I enter a stand of trees. In the dense shade, the ground is soft. When I’m sure no one can see me, I dig a hole. The soil is loamy. Its fecund odor reminds me of spading earth to plant tomatoes, peppers, and beans for our garden. And how, after the seeds were planted, we looked forward to the harvest. I dig faster.

A cow groans, and others join in. I gently place the bag into the hole and spoon dirt over it. With each scoop my breath quickens. By the time I’m finished, the spoon is coated with damp earth, and nausea from my fruitless pregnancy returns. I stick the handle into the ground next to the grave. I stop short of saying a prayer. Looking at the scene, I’m caught between laughter and tears. I vomit behind a stand of rhododendron.

By the time I reach cottage, the sun is out. The cows are busy chewing. My husband and the dog are sitting on the deck. I settle myself next to him. “It’s gone,” I say. He bumps my shoulder with his. Into the silence a truck rumbles down the road leaving the smell of cow manure and the taste of dust in its wake.

—

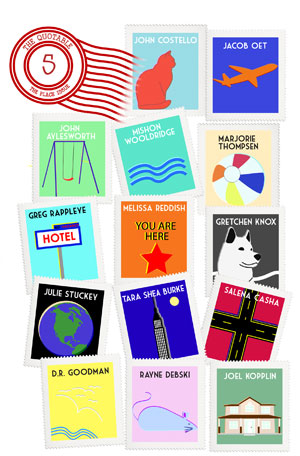

Rayne Debski’s stories have appeared online in Necessary Fiction, flashquake, Rose & Thorn, and The Greensilk Journal, and in print journals and anthologies. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net, and has been selected for dramatic readings by professional theatre groups in New York and Philadelphia. She is the editor of a short fiction anthology forthcoming from Main Street Rag Press in August 2012.