I went to find Dave at the single-wide trailer where Shari and Frank were living, but I was too late.

Frank called out, “Hey, buddy,” as he backed his white, sixties Firebird down the driveway. He pressed a dash lighter with one hand to the cigarette in his mouth. His other hand rested on the wheel. He wore a tasseled calfskin jacket over a white cable sweater. Around his neck hung a leather medicine pouch. Shari sat beside him with her knees folded against her chest. Her long, dark hair was her proof to others that she was a Nez Perce Indian, except she wasn’t.

Frank nodded blond hair from his eyes. “We’re going out to get Dave.”

“He left Dave at the old missile silos last night,” said Shari, leaning over Frank.

The Titan missile silos were buried in the foothills outside of Boise.

Frank touched his medicine bag. “He stole my medicine.” Frank called his drug stash his medicine, but he kept herbs, small stones, and a coyote tooth in the medicine bag.

I asked, “Have you heard from him?”

“He knows how to take care of himself.” Frank’s voice was angry.

“Get in,” Shari said.

I crossed in front of the rust-tinged hood. Shari held her hair out of the way and sat sideways to let me in through the folded-forward bucket seat. Her bare fingers stuck out from the sleeves of a too-large, fleece-lined jean jacket. She settled back into the seat as soon as I was inside. The car smelled of cigarettes and wet leather.

I asked Shari, “Dave wanted to stay at the silos?”

“I don’t know,” she said.

I shivered. “Are you going to call his parents?”

Shari looked back at me. “And tell them what?”

Black asphalt met gray sky between the red seat backs. White snow covered scrub brush and desert.

I asked, “Why did he end up out there?”

“Dave wanted to trip someplace new,” Frank said.

“You dropped and left him?”

“I left him,” Frank said. “All of my stash is at the silos with him.”

“You shouldn’t have left Dave.” My voice tightened. Dave and I planned to leave Boise together for someplace where we could start new lives, before we turned twenty and lost all chance for a future.

This was in December. I’d met Frank at Shari’s in late spring, when they were feeding stray cats. Shari’s cat had run away. Frank was tall and skinny and a few years older. We smoked hashish and talked about peyote and cats. Frank knew a lot about cats, from when he’d worked at an animal shelter. He kept living with Shari after they broke up that summer. He had nowhere else to go, and she didn’t want to be alone.

“Are you comfortable?” Shari asked.

“No.”

I waited for her to move her seat forward. She touched a button, and the speakers blared angry talk radio. She pressed buttons, finding a country station and a Spanish station, until Frank turned the radio off.

The winding highway cut through the hills, Red rock showed like blood vessels where the hillsides had been exposed. Loose snow sifted across the roadbed. The hilltops were piled with snow and the sky was a pale jumble of clouds. The world spun beneath us. We were merging with the white background.

“We’ll never find Dave,” I said.

“Don’t say that,” Shari said, her voice low.

“What a shitty day,” Frank said.

The Firebird slipped left and right on the access road from the highway. I huddled for warmth. Shari twisted her hair to one side. Dave liked to tease her that she was going to pull her hair out.

Dave and Shari, I’d known them forever. In third grade, Shari’s father left her mother, and Shari told anyone who listened that he wasn’t her father. When he was sixteen, Dave moved out of his parents’ house to escape his father’s rules about music, drugs, and men. When Shari turned sixteen, she left home and stopped using her real name, Charlotte White. Her mother screamed that she was a slut as we carried a duffle bag full of clothes and a box full of her photos and books on the Nez Perce down the street.

That night in my bed, Shari told me a Nez Perce creation myth. When she finished the story, she rolled on top of me and whispered, “We are waiting for someone to make us new, for blood to make us new.” Her breasts and her hips pressed down through her nightgown onto me. I said nothing and kissed her, but nothing more happened. She left the next morning.

A gray, chain-link fence bordered the abandoned missile complex. The low buildings and straight fences squared against the hills. Snow hid the concrete silo doors, which covered gaping holes in the earth. Everything was gray where the snow wasn’t turning it white. People went to the silos to drink, shoot guns, look for anything to steal, blare loud music at the desert, and explore the tunnels.

“Maybe he walked home,” I said, my breath puffing in clouds before my face.

“Maybe,” Shari said.

We walked around for an hour. Frank looked inside the buildings. If Dave had left footprints, they were covered by the snowfall. The air rasped my throat and lungs, and I stopped calling out.

“Dave’s not here.” Frank laughed at his joke.

I shivered under my surplus Army jacket. “It’s too cold,” I said.

“I’m cold,” Shari said.

“I’ll start the car,” Frank said.

“Take another look for Dave,” Shari told me. “The heater takes time to warm up.”

“Don’t leave without me,” I said.

“I won’t,” Frank said.

“I’ll come with you,” Shari said.

“I promise,” Frank said. He lit a new cigarette off his old one and flicked the butt into the snow. I walked toward one of the buildings. Frank wouldn’t leave both of us behind.

Shari offered me a cigarette. We watched a jackrabbit run away. Little bursts of snow rose behind the rabbit’s feet into the distance.

The car started and turned off. There was a screeching sound after the engine stopped, like a worn fan belt, but worse. Frank lifted the hood and there was a sound of tired metal moving. But there was another sound. The engine wasn’t running. I walked to the car to see. Shari stood a ways away. I didn’t want to walk back to town.

Frank was staring at the engine block.

“There’s a cat,” he said.

Stray cats lived at the missile silos, surviving on rodents and other small creatures. One had crawled onto the engine while we searched and had fallen asleep. The first warm sleep of that cat’s life. Then the car started. The fan belt had pulled the cat’s hindquarters into the machinery. The cat’s back legs were crushed, and its back was broken.

Frank reached forward with both hands. He gripped the cat’s head. The wailing stopped soon after that.

He wiped his hands on his jeans. “I have some rags in the trunk. Get them.” Frank took a Buck knife from a leather holster on his hip.

I took his keys from the ignition and opened the trunk. Shari was sitting against the back of the car and smoking. She looked away when I took the pile of red oil rags.

Frank grunted as he worked. There were other sounds. He threw pieces of something away from the car. He never threw in the same direction. The dark clumps stained the snow where they landed. Frank cleaned the knife and his hands in snow.

“Give me the rags,” he said. A heavy, warm smell turned my stomach. He wiped his hands with the rags. The snow was red, like Frank’s sweater, like the cut hillsides.

“Try starting the engine,” he said.

I slid into the uncomfortable groove worn into the front seat and turned the ignition. The engine screeched for a moment before producing a throaty, grumbling sound. The hood clanged shut.

Frank climbed into the back seat and curled on his side. His hair fell over his eyes. His fingers curled like claws. He said, “Goddamn. My hands half froze.”

“Fuck,” Shari said. She flicked away her cigarette and slid down into the Firebird.

“I’ve always loved animals,” Frank said.

I drove back to the highway and read the signs aloud. Orchard was five miles away, close enough for Dave to hike to. Boise was twenty in the opposite direction.

“Forget Dave,” Frank said. “Go back to Boise.”

“Fuck Dave. I hope he’s dead,” I said. “Dave, he left me outside the night I threw up all over his bathroom. I almost froze to death.”

“Don’t let it get to you,” Shari said. “People forget things.”

I drove through the cracked desert hills toward Boise. Cold air trapped smog over the valley. The valley had been carved by glaciers and the ancient inland sea and years of wind. The bones and blood of the earth were laid bare where the road was cut. You couldn’t see Boise, only the surrounding foothills. In summer, the hills are tawny lumps like some creature’s fur. That afternoon, the setting sun discolored the snowy hills.

Shari moved her face next to mine. Her breath was hot and smoke-smelling. “Dave wouldn’t have left you to die.”

The road straightened to take us west into the dying sunlight. I looked away and shut my eyes. Shari clasped my hand, and I opened them.

I remembered the creation story that Shari had told me. A giant rampaged across the countryside. Coyote, the trickster god, captured and cut apart the giant. He threw the pieces of the giant’s body in different directions. Wherever Coyote threw a piece, a new tribe sprang up. He never threw in the same direction. From the giant’s blood, he’d created the Nez Perce.

That’s what the hills looked like, like they were stained with leftover blood.

I waited for blood to wash the sky, but Coyote never came. We were not giants he would carve into pieces. We remained in a place that would as soon forget us, as I had tried to forget it.

—

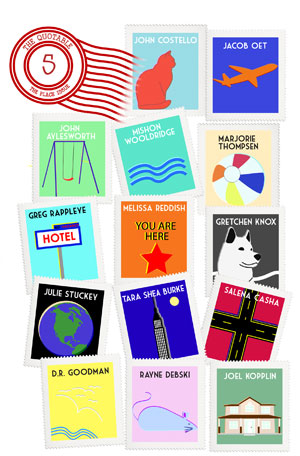

John Costello grew up in Idaho and Alaska. He lives in Seattle with his wife and three cats. This is his first fiction in print.