Josephine, or Jo as she likes to be called, has a terrible sense of direction. She gets lost going to the bank, the post office, the grocery store, even the 7-11 on the corner with her favorite orange Slurpees. All of the roads look the same to her; landmarks are meaningless piles of wood or concrete. She turns right when she should turn left, goes straight when she should turn around, and often feels the sickening knife-plunge of certainty when she hits the outskirts of town and realizes she’s been heading in the wrong direction. It sometimes feels as though the world is being erased behind her—each rut in the road removed as soon as she bumps over it, only to reappear in her mind when she loops back around.

She has developed elaborate tricks for finding her way home, such as drawing a decreasing series of numbers on stop signs, light poles, and small dogs tethered to tree trunks, creating a trail of breadcrumbs she will recognize. She is often late for work restocking books at the library, but it is a boring job. There are always more books to restock, an endless pile on the little cart she wheels from stack to stack, so there is no point being on time. Her friends often make fun of her.

Poor Jo couldn’t find her way out of a paper bag!

Poor Jo—if she ever gets married, she’ll have to handcuff herself to the man so she doesn’t forget and wander off.

They laugh their high-pitched laughs that remind Jo of sharpened teeth and tell her they are only joking.

One day she runs into the little sign wishing she would come back soon and thinks, why not keep going? People travel every day. Maybe she can find a place she will remember, a place that will imprint a map in her mind. So she keeps driving.

After a few minutes she realizes she can’t remember her home very clearly. She pictures the knobby plaid couch and the bowl of beaded fruit on the kitchen table, and then, as she drives further away, the sweep of blue curtains in the window, and then nothing at all. She takes this as a sign that she is headed in the right direction.

She stops at sprawling rest stops in Georgia and discovers dozens of different pecan products. She continues through the Carolinas and Virginia, stopping briefly around the Eastern Shore of Maryland. She wants to see crabs, but instead she finds geese, herons. She stops at a low-slung brick restaurant serving Steaks-Seafood-Pasta. When the waitress tells her they don’t serve crab, a man in the adjacent booth gives her directions to an all-you-can-eat crab buffet that she knows she will never find. Already the twists and turns accompanied by the easy sweep of his hands are disappearing from her mind. She thanks the man and eats her fettuccine alfredo.

She reaches the endless mountains of Pennsylvania with town names like Tunkhannock, Towanda, Wyalusing. She finds a dingy motel on Rt. 6 where a gum-snapping waitress serves her a huge slice of pie for a dollar fifty. She drives down a dirt road with a stream running beside it and sees a family walking down the road, the father shirtless, the children in identical blue swim trunks. There are red farmhouses, gleaming silos, the occasional cluster of goats. She passes semi-trailers carrying sand, water, acid, and sometimes nothing at all. Several times she must stop for roadwork, and each time a thick man in a yellow vest flicks his wrist to find another route. Since she has no clear destination, Jo doesn’t panic as she is forced down thin, looping side roads, the pavement falling away in chunks near the edge.

She continues to the fog-smeared towns of Maine and finds a whale-watching cruise. Next to several tourists in red and blue windbreakers with children clutching digital cameras far too expensive for their stubby fingers, Jo watches two whales swim right up to the side of the boat. For a moment, she is thankful for the obliteration of her memory. She waits for them to break the surface and arc a beautiful spout of water, but they never do. Underneath the water, pale and ghostly, they glow.

Jo means to continue up into Canada to try some maple syrup, but instead she drives south and west. In the fields of Belvue, Kansas, her car breaks down. It was only a matter of time before a gear slipped. She walks down a small dirt road and sees a man idling on a lawn mower. She asks him where the nearest hotel is. Her hair is disheveled and her eyes rimmed with black. The man holds the soft white flesh of her wrist and forces her to stop. He leads her to a tan farmhouse and places her between soft blue sheets.

When Jo wakes up, she notices gauze-like curtains ruffling against an open window. Sitting up further, she touches the cream-colored comforter, the light blue sheets beneath them. The sheets are not as soft as she remembers: they are starched stiff and both ends are tucked underneath the mattress. She wiggles out of them carefully. Glancing around the small room, she sees a bookcase, a braided rug across the hardwood floor, and a small, frosted light above her bed.

There is a knock on the door, and then the same man enters with a tray. Jo has never seen a man whose face was quite so square. There are the beginnings of fine wrinkles near his eyes, and his hair is cropped close to his head. He is the kind of man others would call stocky, but Jo prefers sturdy. She’s never really cared for men who bend like willows. She prefers men more solidly anchored to the ground.

“Thought you might like some breakfast,” he says and places the tray across her lap. “You seemed awfully tired.”

“Thanks. What’s your name?”

“Benjamin.” He wipes his hands on his jeans and reaches out to shake hers.

Jo waits for Benjamin to ask her name, but he doesn’t. He just stands there and watches her eat. When she finishes, he takes the tray and closes the door gently behind him. On a small chair beside the bed, there is a towel and washcloth. Jo opens and closes doors until she finds the bathroom, where she takes a long, hot shower. Hanging on the back of the door are a pair of jeans and a sleeveless blouse. The blouse is only slightly loose on her, but the jeans fit perfectly. She wonders what other needs this strange man has anticipated. She knows she should be wary of him, of a serial killer basement hidden beneath the floorboards, but Benjamin’s every move has the air of a large man trying not to crush something delicate.

Downstairs, she finds him washing her dishes. When he sees her, he turns off the faucet and leans back against the sink.

“Hope the clothes fit alright. They were my sister’s.”

Jo notices the past tense, but it feels much too intimate a question to ask right now.

“I had your car towed to Bert’s Auto. Hope you don’t mind. Turns out your timing belt snapped. I can take you up there this afternoon.”

“Thanks, again.” Jo rubs the silky material of the blouse between her fingers. “Why are you doing all this?”

Benjamin shrugs. “Don’t know. Just feel like it, I guess.” There is a brief silence and Benjamin clears his throat. “So, do you know someone here?”

“No,” she says. “Just traveling.”

“Where are you headed?”

Jo shrugs, feeling suddenly shy. There is no way she can explain why she has been drifting from town to town, unmoored. If she tries to explain how objects lose their permanence as soon as she turns her back, he would just roll his eyes and tell her to learn how to read a goddamn map or explain, as though talking to a child, how nobody’s memory could be that bad. She just needs some mnemonic tricks like Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally. That was how every other person from her mailman to the 7-11 clerk had responded when she first tried to explain her bizarre affliction. She’s come to realize that most people have an unshakeable view of the world, and she doesn’t fit within it. So now she just keeps it to herself.

“Well, if you don’t have any particular place in mind, why don’t you stay here and rest a bit longer? No one’s using the guest room, so you’re free to stay a couple more days.”

“Okay,” Jo says. Resting for a couple more days does sound nice. The road will still be there, after all.

Over the next couple of days, Jo learns more about Benjamin. He drives an hour and a half each day to the Hostess factory where he supervises the line. Jo can imagine the donuts—chocolate and powdered and glazed—all ferried down belts to be packaged in gleaming white bags. It’s mostly all done by machine now, he explains, so there isn’t much to the job. She asks why he doesn’t live closer to work, and he explains how the farmhouse used to belong to his parents. When his father died of heart disease and his mother succumbed to early onset dementia, he and his sister meant to put it up for sale. The second day of her visit, as she was driving to the real estate office, she was killed by a garbage truck that ran a red light. Now, the house is all Benjamin has. Everything else has been shucked from his life.

When he asks about her parents, Jo clamps her mouth shut. She can only remember pieces of her childhood, brief images unattached to anything else: a wooden mailbox with their last name etched onto the side, a driveway filled with small gray rocks and the occasional glittering white rock that Jo thought was treasure. She can’t remember the house at all, and whenever she asks her mother, the description seems to change slightly each time. Both of her parents moved out west to Arizona, shedding furniture and decorations in their wake in an effort to live a smaller, more simplified life. Jo is embarrassed to admit that she can’t even remember whether her mother has brown hair or blonde hair (it is probably gray now, anyway) until she looks at the photograph of all three of them taken at the Smile Hut when she was fifteen. She keeps the photo in her wallet for reference so they don’t disappear completely.

Each night Benjamin makes dinner, roasted chicken or pasta with meat sauce, and tells her stories from his life. He always leaves a small silence at the end in case she wants to tell one of her own. After the second week, instead of walking into the guest room Jo is starting to think of as hers, she opens the door to Benjamin’s bedroom. Quietly she climbs into the king-sized bed. The sheets are just as stiff as the guest bedroom. She tells him about her life, what she can remember up until that point. She tells him about traveling all across the country and how she could never return to the places she’d been, including her home, because she can no longer remember the way. Afterwards, he is quiet for a while.

“Well?” she asks. “It’s ridiculous, right? Unbelievable?”

“We all have something,” he says and traces an invisible line down her thigh.

For a couple of weeks, everything Jo needs—toiletries, books, the ingredients to chicken divan—Benjamin brings back for her. The day after she slept with him, she was preparing a trip to the mall to buy some clothing, but Benjamin had grabbed her wrist, just like when she had broken down in front of his house, and asked her to stay. His eyes were large and they trailed down to his sister’s gingham shirt. “Whatever you need,” he said, “I can get for you.” Sometimes Jo imagines that when he saw this woman in his sister’s blouse and jeans standing there, suddenly and irrevocably whole, it was an image he could never let go.

And for a while it was okay. But now, her memory is getting worse. Earlier that day she walked into the front yard, looked up at the white-hot smear of sky, and felt the pitch and stagger-step of panic before she turned and remembered the house, how to get back inside. At the same time, she can hear her feet tapping the rhythm of the road: the steady ca-chunk, ca-chunk of the highway that hasn’t been paved in years, the rat-tat-tat-tat when she drifts into the grooves lined into the median. She thinks about all the places she hasn’t seen and is surprised to find the aching yawn of desire bloom inside of her. It is only a matter of time before she walks out the front door and drives through the fields of Kansas and out of Benjamin’s life forever.

Later that night, Jo finds him stirring a pot of chili for dinner.

“I can’t stay locked up here.”

Benjamin continues to stir without looking at her. “And a map won’t help?”

Jo shrugs. “The streets don’t mean anything to me. They don’t tell me what I’m trying to find.”

He pulls out a sheet of paper and spreads it across the kitchen table. It is larger than the table, and Jo wonders where it came from. He pulls out pencils, pens, markers, a compass and ruler. With aching precision, he begins drawing a map. She can see lines and circles begin to take shape: first, his house, and then the street leading down to the corner mart. She can see the post office, two grocery stores, the Super Wal-Mart, and their neighbors’ houses. More of the same, she thinks to herself.

He asks her about the house where she grew up, where she had her first dance, her first kiss. She can’t remember and waves her hands in the air, stirring the fog of her memories. His questions get more specific. Where was a place you made a promise you later broke? When was the first time you knew your mother would eventually die? Answering each question solidifies her memories, pulls them into light. She describes the taste of her mother’s chicken divan, the nutcracker suite her grandfather kept on the mantle year-round. Benjamin pulls out interstate maps, guides to every state. He runs his finger down passages on places of interest and asks her follow-up questions. He finds even more obscure books that zoom in on counties and streets, that pan through the ever-shifting landscape of mailboxes, that hover over backyard barbecues and record tree branches stripped into swords, a series of captured moments that were once true. Every so often he thrusts a book at her with his finger jabbing a photo and she cries yes, that was my friend Sallie’s house or that was the hospital where I was born.

With each nod he draws more lines, the map growing larger and so finely detailed until it is a tapestry with a million silky threads, a tree trunk carved with the rings of her life. When she looks at it, she can see their house and through the tiny window, the packet of seeds on the dresser he meant to plant later that day.

He creases the paper into an intricate series of folds. Only a small square is now visible.

“Just refold the map to show where you are.” He hands her the hard lump of paper, heavy from such accumulation.

“Test it out,” he says. “We need some stamps from the post office.”

She traces her finger down the street from their house until she finds the right building. It is all so simple. She gets in the car and drives slowly, pausing every few moments to check and recheck the map. Cars honk at her in intersections, but she ignores them. Finally, she makes it to the post office. Once she is back in her car, the route back wavers like lines of heat off asphalt. She studies the map, finds Benjamin’s house—our house, she thinks—and the way back crystallizes. She can clearly picture the yellow farmhouse with the meadowsweet planted out front. Benjamin, too, she can remember: the curly brown hair on his back and chest that reminds her of seaweed, the way he holds his hands like two meaty paddles he hasn’t yet learned how to use. She sticks the map on the dashboard and glances at it every now and again to make sure she is headed in the right direction. When she makes it back home, Benjamin is visible through the window. He smiles and waves, and her breath feels heavy and warm inside her.

Days pass like this. The map is fine, amazing really, but having to work her way through the intricate system of folds to find the one area she needs is tiresome. One day she leaves the map in the car and feels a small knot of guilt at how much lighter she feels. Can she say for certain she will never lose the map, either leaving it on the counter while paying for gas or letting it tip out the car window? She needs something quicker, lighter, more permanent. She looks down at the fine creases on her palms that a fortune teller would use to link the past and the future, and she has an idea.

In the living room, she pulls out the markers Benjamin used to create his map. She draws a map on her body, starting with the very tips of her fingers. There are lines like capillaries leading to all of the places she has been. She winds a pink path down her stomach, circles the small hump of her thigh. She has symbols for all of the important places. A circle for her childhood home. A triangle for the hospital where she was born. A heart on her wrist for Benjamin.

After she finishes, she walks outside and drives to the grocery store. She feels a tenuous system of roots winding their way around her, each line leading her back. She buys eggplant and breadcrumbs and sauce, a watermelon for desert. All the while she thinks about what jobs she will apply for, what she actually wants to do with her life. As she loads the bags into her trunk, it begins to rain. No, she thinks, but it is too late—the lines blur and slide down her body. She hadn’t used permanent ink. The heart too smears into an angry red lump and she can no longer remember what it is supposed to mean. She panics, opens the trunk, looks at the groceries she just purchased. They are strange, meaningless. Who needs an entire watermelon for one person?

She closes the trunk, gets into the car, and drives, feeling an itch at the small of her back that she can’t quite reach. It blooms, a soft beckoning of nail, until she doesn’t notice it any more.

—

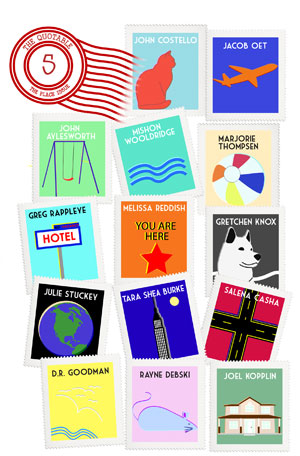

Melissa Reddish graduated with an MFA from American University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming from decomP, Printer’s Devil Review, and Prick of the Spindle, among others. She is also the co-faculty editor of Echoes and Visions, the student literary publication of Wor-Wic Community College.